By Joanna Cohan Scherer

Boorne's Permission to Photograph

Boorne had tried unsuccessfully to photograph the Medicine Lodge ceremony in previous years and was "extremely anxious" to photograph the piercing. While he nowhere explicitly states why he was so keen to take these images, it must be assumed that he was challenged to be the "first" to photograph it and as a commercial photographer the idea of marketing the images was an important factor.4 In 1893 Boorne wrote:

"I well remember a visit paid to the Blackfoot Reserve just after the [Riel] Rebellion in '85 when the famous chief, Crowfoot was alive, for the purpose of securing, or rather trying to secure, some photographs of the great annual 'sun-dance.' I was particularly anxious to get a shot at the 'torture,' which I was informed had never been actually photographed, and it was not photographed then, as you will see, although I managed it next year, when I knew the Indians better. I must digress a little here, to explain that the Indians are the most superstitious of people, and in those days it was a very difficult matter indeed to get one to allow a photograph to be taken, even with the offer of money. They were beginning to know the sight of a camera, and understood what it was for, but what they could not comprehend was how a 'spirit picture,' as they called it, could be taken of them without taking something away from them; in short, they believed, as many do even now, that the act of photographing them would shorten their lives, by robbing them of a part of themselves. I knew something of this, but I did not know the Indians as well as I do today, and thought that if I sailed boldly into the 'medicine lodge' and set up my camera, a few plugs of tobacco, etc., that I had with me, would make it all right. I marched in and the first part of my program went off all right — and then I sailed out, and quickly too. The Indians were at first somewhat taken by surprise at what they no doubt considered an instance of the white man’s sublime cheek, but no sooner was the camera in position — before I could focus, or even get my head under the cloth, — the racket began. They crowded around me, threw a blanket over the camera, yelled, and shouted, danced and actually fired guns off over my head to scare me. I was scared all right, and only too anxious to see the outside of that lodge; and in quicker time than it takes to tell, I saw the outside, camera and all, assisted by three or four lusty young 'bucks' in gaudy paint and feathers. Even then they were not satisfied, for they wanted to hustle me off the reserve altogether, but some of the older men interfered, and old Crowfoot — peace to his memory! — ordered them to be quiet; and they obeyed him like lambs. I was thankful at not having my apparatus smashed, but took the nearest approach to a revenge that I could, for I succeeded in getting a snap shot at the outside of the medicine lodge, assembled crowd and all, before leaving.

"Next year, I determined to try different tactics, and a different tribe, and going south to the reserve of the Bloods, camped on the outskirts of the immense Indian camp, about three weeks before the actual dance began— for they take several weeks preparing for it — and spent everyday in walking about amongst the 200 or so teepees assembled in the bottom, familiarizing myself with them, and they with me and my camera. Next, I secured the services of an Indian interpreter, who had worked for the N. W. Mounted Police, and promising him a small bonus for every successful view I secured, left him to make all necessary arrangements. In this way I managed to get a very fair collection, and when the grand day arrived the Indians were accustomed to seeing me and my camera, and only occasionally amused themselves by setting a few of their thousand and one dogs at my heels.

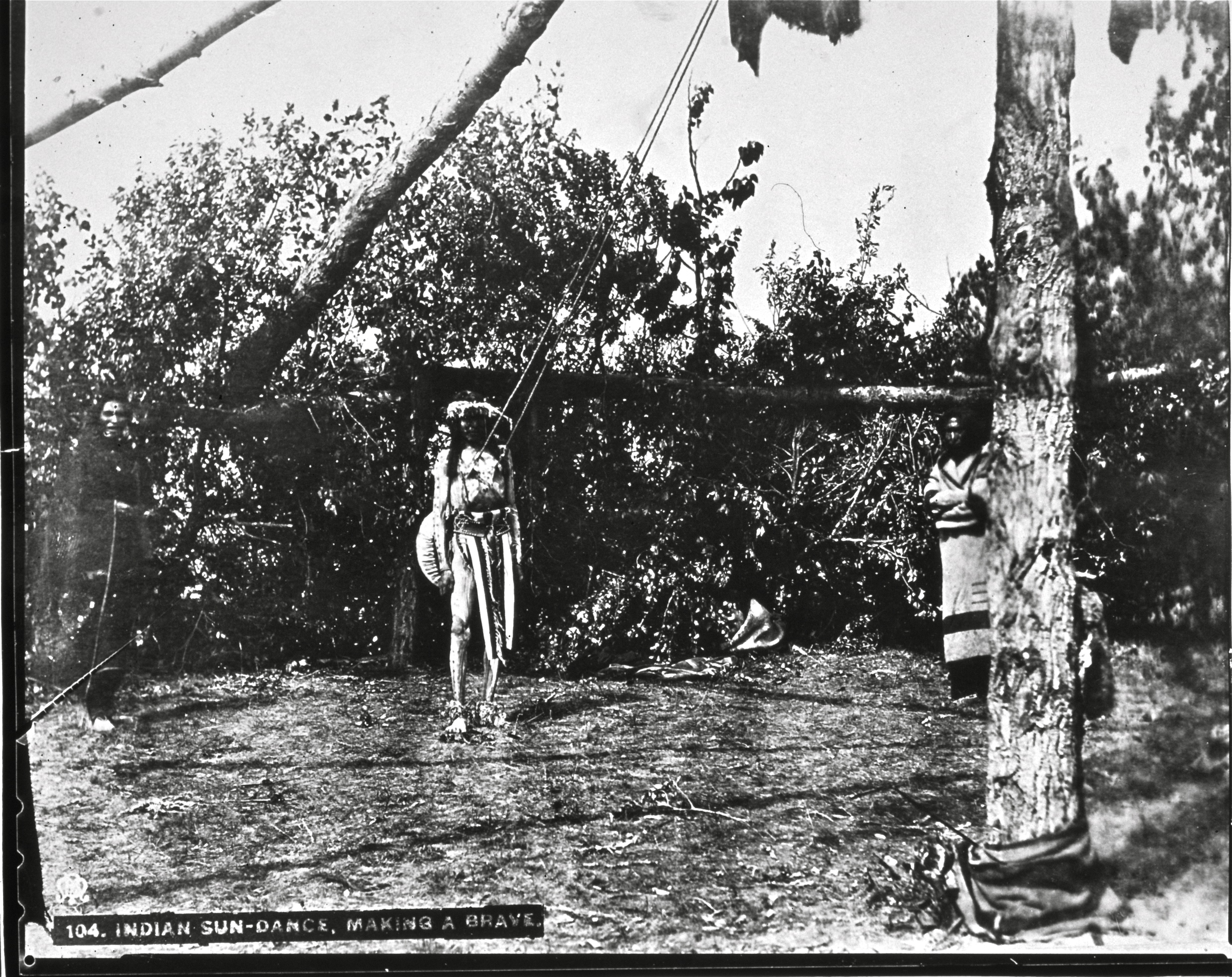

"The night before the great dance, 5 I was called to a pow-wow in the head chief's (Red Crow's) tent, and there found seven other minor chiefs assembled. [Some of these chiefs were One Spot, White Cap, Bull Shield, and Heavy Shield.6] My interpreter ('Wolf-Shoe' by name) had arranged everything, and it was decided that I should make each of the minor chiefs a present of two dollars, and Red Crow three dollars. [Boorne gave assurance through the interpreter to the chiefs that no mental or physical harm would come to the participants as a result of being photographed; cp. MacFarlane (1939:17). 7] I promised tobacco on the morrow, this was overlooked, and they gave me formal leave to enter the sacred medicine lodge and do my worst. And here I may say that this promise was faithfully kept in spite of the very loud and angry expostulations on the part of some young bucks and all the old squaws. I distributed some tea and tobacco in the lodge, and a little more backspeach to two of their braves who were undergoing the torture, and secured some very good negatives of the preparation of the braves for the torture, [Fig. 1] and of the torture itself. Every now and again a fiery young blood [sic] would jump up and hold a blanket in front of the camera, but Red Crow kept faith with me well, and shut him up at once. Nine braves were tortured that day" (Boorne 1893:272-273).

An article in The MacLeod Gazette dated Tuesday, August 2, 1887, gives the following account of this event. 8 Although not written by Boorne it appears to be an eyewitness account:

"Sunday was supposed to be one of the gala days of the Sun Dance, and a lot of the wicked citizens of MacLeod strung themselves toward the Blood Reserve at about ten o’clock in the morning […] In the midst of this large concourse of tents stands the centre of attraction the Sun Lodge […] About the only thing which can excite one's curiosity is the making of a brave. On Sunday one Indian went through the ordeal […] the one who finally submitted to the operation offered himself for $3. Mr Boorne, the enterprising photographer, had bargained with the buck for that amount. After about an hour of weary waiting a ghost-like figure glided into the lodge, closed his fingers over the $3 and glided out again. Another hour and a half and the victim had not returned, and both the photographer and the people began to think, after he had the money safe in his pocket, he had changed his mind. Everyone left the lodge to start for home, and just at that moment the ghostly apparition reappeared ready for the fray. He was powdered all over with polka dots of yellow which made him look something like a hail storm. His only clothing was a breechcloth. [The participant was covered with white paint and yellow ocher dots from head to foot, had yellow streaks on his whitened face, and willow wreaths with leaves on, twisted around his forehead, wrists and ankles.9] Lying on his back on the ground, three or four Indians got about him, and the operating began […] Before the operation began, an old party got out and counted the young man's coups. The list was not a very long one. He stole a gun, and he stole some horses, and he stole some arrows […] The young man then blessed the old fellow, threw his arms around the medicine pole, and prayed to the sun. […]"

Next Section: The Dance Photographed

4 The Calgary Tribune, Friday, August 26, 1887, reported an account of Boorne’s visit to William Pocklington, the government agent on the Reserve, which was about nine miles from the Medicine Lodge camp. Boorne had gotten a thorough soaking while crossing the swollen junction of the Belly and Kootenai Rivers and spent several days at Mr. Pocklington’s drying out. Boorne noted that Mr. Pocklington asked him for pictures of the “brave making” and he promised him he would get them for him if he could (Boorne 1887).

As early as September 23, 1887, Boorne was advertising the sale of his Sun Dance photos in The Calgary Herald: "Photographs \ An immense assortment of \ NEW LOCAL \ and \ Indian! Sun Dance \ and other views \ Call and see our show room \ We pack safely and pay Post- \ age on all over $2.00 worth \ A SPECIALTY \ Selected views in very choice imported French \ Mounts, and Oak and Gold frames for house Decoration \ $3.00 and 4.50 Complete \ BOORNE & MAY \ Portrait and Landscape Photographers, Calgary"

5 In an account by the photographer published in The Calgary Tribune, August 26, 1887, he says this meeting took place in the morning.

6 Boorne, The Calgary Tribune, August 26, 1887.

7 The 1939 MacFarlane publication appeared also in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Quarterly, April 1940. The author has not been able to track down the source of Boorne's manuscript that MacFarlane used, but it differs in certain details which will be noted when they appear important.

8 This article was probably written by the editor of The MacLeod Gazette, C. E. D. Wood (personal communication Hugh Dempsey, October 6, 1994).

9 Boorne, The Calgary Tribune, August 26, 1887.

McClintock (1910:319) describes the Sun Dance participants of the Montana Blackfeet as having their bodies covered with white clay, painted with black streaks on their cheeks, representing tears, and with wreaths of juniper on their heads, and sage leaves tied around their wrists and ankles. Body painting was and is today part of the daily ritual of the Medicine Lodge ceremony.